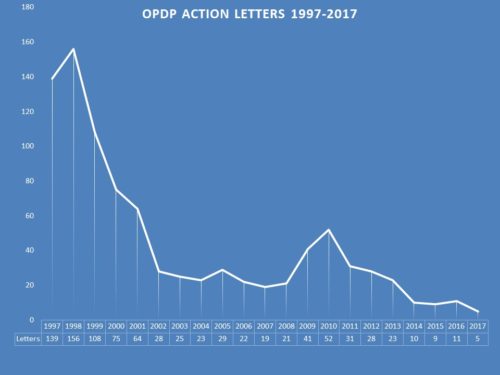

It goes without saying that enforcement by FDA’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) as identified through regulatory action letters (warning or untitled) over the past few years is a mere shadow of its former self. Enforcement was once robust, peaking at 156 letters issued 20 years ago in 1998. The year before last, the number had dropped to 5, only increased to 11 by a December surprise when 6 letters were suddenly issued within the month. So far this year, there has been only one.

Many have speculated on the reasons for the drop, and FDA has provided nothing specific in response to inquiry. With enforcement actions so few, it pays to look closely at the circumstances that have moved FDA into action.

Of all the major violations that generally occur with pharmaceutical product promotion – Omission or Minimization of Risk, Superiority Claim, Broadening of Indication, Unsubstantiated Claims, Promotion for an Unapproved Use and Promotion of an Unapproved Drug, the one that ranks the highest in terms of number of violations is by far risk, the one that has ranked the smallest has been Promotion of an Unapproved Drug. FDA regulations state that a drug sponsor, or investigator, or anyone working on their behalf, should not indicate that a drug is safe or effective prior to its approval by the agency.

How uncommon is it? If you look all the way back to 2004, there have been only 14 letters issued covering 15 different communications vehicles for promotion of an unapproved drug, which averages out to one per year.

However, they did not come out at the rate of one per year – in fact, over one-third of them came out during 2016 and 2017. While comprising only 4.6 percent of all the letters issued since 2004 have involved promotion of an unapproved drug, 28 percent of the letters issued since 2015 have involved promotion of an unapproved drug. Either it is happening more often, or it is something about which FDA still cares a great deal about, even in an era of diminished enforcement actions.

It may be worth noting that, with one exception, nearly all of the letters were sent to entities that are lesser known.

What trips the regulatory wire? FDA tends to look at the totality of a presentation when assessing promotional communications – meaning the agency looks to see if there are factors which contribute to an overall impression rather than just an individual statement. In other words, use of the brand name, in conjunction with other aspects of the way the drug is being talked about (such as being displayed next to already approved drugs) could create the impression that a drug has been approved. That said, of course, specific language – like indicating that a product has fewer safety issues than the current treatment (“the drug is safe” and “the drug is efficacious”) – could also be a cause of concern. Common to the violations cited in recent letters were present tense “conclusory” language such as “accurately detects” and ” is a unique long-acting formulation”.

Are the violations predominant in one kind of media over another? Over the span of time, violations have occurred as oral statement from clinical investigators during medical meetings, on exhibit panels at medical meetings, in brochures and in videos. Of the total number of 15 letters, 9 involved a website, making it the most common communications vehicle involved in promotion of an unapproved drug. That is a place one might think it would have been the easiest to prevent, especially given the fact that oral statements are harder to guard against when it comes to any violation. It may just be an indication also of the fact that websites are easier to monitor and detect.

There has been some speculation that FDA is centering its enforcement in areas where there is highest risk – which would include things like a product with serious potential adverse events being promoted in a way that omits risk information. When it comes to pre-approval promotion, not only has the proportion increased, but the rate of such violations as well. Those two facts combined might lend the impression that this is a violation in which FDA is more interested. And given the prominence of the category as a subject of FDA enforcement, communicators should take note.

Photo by Goh Rhy Yan on Unsplash